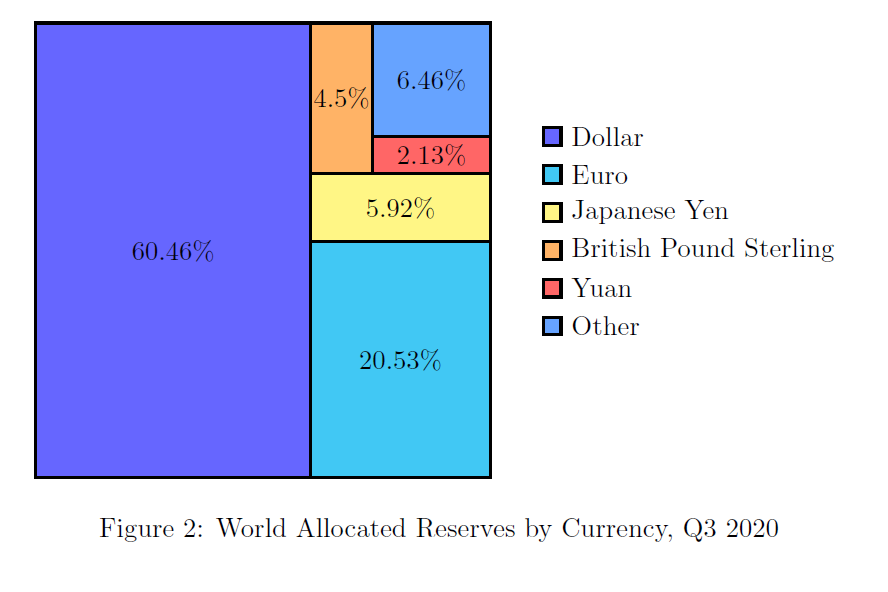

Economic theory tells us that money has three primary functions, to act as a medium of exchange, a store of value and a unit of account. The US Dollar not only excels in these three functions, but it also dominates against every other currency globally. In 2019, the greenback was involved in 88% of international transactions and 40% of the world’s debt is issued in dollars. Amazingly, in 2018, the banks of Germany, France and Britain held more liabilities in dollars than their own currencies. The dollar excels as a medium of exchange, both in the goods and capital markets. Around 60% of total central bank foreign exchange reserves are allocated in dollars. Even during the Great Recession, the dollar strengthened by 22%, despite the crisis originating from the US. The dollar has proved to be an excellent store of value throughout the boom-bust cycle. The dollar also thrives as an invoicing currency, with over 50% of goods imported into the EU being invoiced in dollars despite the Euro being the world’s second most dominant currency. Furthermore, numerous commodities such as oil, gold and coffee are priced in dollars, making it an almost universally understood unit of account. The dollar is irrefutably the king of currencies, but will the effects of coronavirus reaffirm this or bring the dollar’s reign to an end?

Economist Charles P. Kindleberger argued that a dominant currency would actively stabilise the global economy by promoting trade and supporting capital markets in his “hegemonic stability theory”. The impacts of the dollar hegemony prove him right. Take two foreign companies who desire to trade. Two things may stand in their way. A volatile exchange rate between their two domestic currencies, exposing them to foreign exchange risk and the difficulty of trading two uncommon currencies. If both firms use the US dollar, these barriers are eliminated, thereby promoting trade. For this reason, more countries and firms are incentivised to operate in dollars, stimulating global trade and facilitating growth across the world.

Unsurprisingly the US itself can derive some benefits from the widespread use of its currency – it’s so-called “exorbitant privilege”. The dollars reserve status means that central banks and foreign governments flock to buy US Treasuries, driving down the cost of borrowing for the government. Estimates by McKinsey suggest that the US governments borrowing costs have been reduced by 0.5 – 0.6% in recent years due to the dollar’s reserve status. The dollars use in international transactions also provide the currency with greater liquidity, reducing the cost of private borrowing in USD, benefiting capital accumulation, and thereby economic growth.

However, dollar primacy is not without its drawbacks. Continued demand for the US dollar for FX reserves and international trade inflates the currency’s exchange rate from 5-10 percent. This results in less price competitive US exports and more price-competitive imports, contributing to the US’ persistent current account deficit. Furthermore, dollar primacy can lead to the transmission of monetary policy enacted by the Fed around the world. Although this may sound appealing at first, Ben Bernanke argues that we need to ensure the Fed doesn’t become the “world’s central bank”. Take contractionary policy by the Fed. An increase in the interest rate will cause a currency appreciation due to hot money flows. This results in larger debt burdens for emerging market borrowers, with 33% of corporate bonds in EMEs denominated in dollars. This can depress capital accumulation and unintentionally slow global economic growth.

In past global crises, America has successfully coordinated international responses, proving its worthiness as the world’s economic and geopolitical superpower. During the COVID-19 crisis, it has done much the opposite. After botching its domestic response, the Trump administration has failed to support developing economies, erratically cut funding for the World Health Organisation and engaged in a dangerous blame game with China. This glaring ineptitude of American leadership has left a void in global initiative – one many nations will attempt to fill.

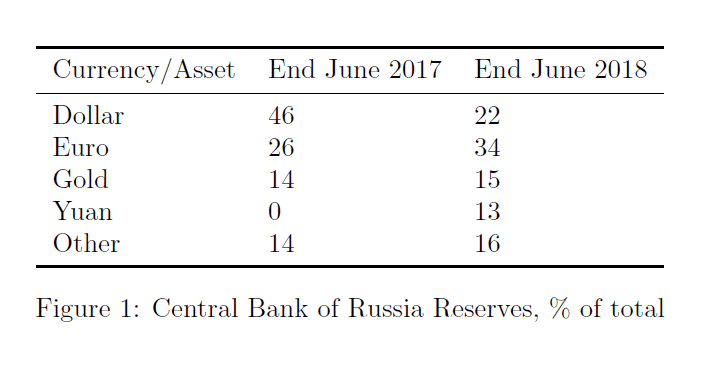

China is hastily trying to reshape its image as the world’s saviour, not the deliverer of its demise. It has distributed vital medical provisions and teams of medical experts to disproportionately impacted regions. Alibaba and Huawei, who have often been cited as henchmen of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), have donated supplies to nations in Africa, South East Asia and even Europe in a bid to win over sceptics. With this reshaping of its image, China will promote the renminbi as an alternative to the dollar. Early signs are showing this at work. In late February, as the virus emerged in Europe, foreign investors poured $10.7 billion into China’s yuan-denominated bond market – a potential new safe-haven asset. Moreover, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has shown restraint when expanding the money supply. The PBoC is reluctant to monetise the Chinese budget deficit or expand their balance sheet, making the yuan an even more attractive reserve currency option. Russia has already begun to de-dollarise parts of its financial system in favour of the yuan. The Russian Central Bank’s holdings of the dollar fell from over 40% in 2017 to 22% in mid-2018, with the central bank taking up a greater position (nearly 15%) in yuan. Russia has also explored settling more of its bilateral trade in its own currency – the rouble, and has even considered issuing its sovereign debt in yuan. Russia has shown that the yuan is a worthy contender for the dollar as a reserve currency – one that other governments and monetary authorities should start to strongly consider.

In early May, the PBoC began trials of its new cryptocurrency – the e-RMB. It is set to be the first digital currency operated by a major economy and represents a huge step away from the dollar hegemony. Chinese officials are unashamed to reveal the true intentions of this technology. The state-run China Daily reported that “A sovereign digital currency provides a functional alternative to the dollar settlement system and blunts the impact of any sanctions or threats of exclusion”. Its adoption may be appealing for other nations (or firms) trying to distance itself from the political volatility in Washington DC.

However, the ugly side of the autocratic state should not be ignored. Many developing nations are already weak from Chinese “debt-trap diplomacy”. The pandemic may exacerbate this with China providing debt relief at the cost of sovereignty – already seen prior to the pandemic in Sri Lanka and Djibouti. Furthermore, the power continues to undermine the independence of Hong Kong; a move that may be financially motivated, given that the financial centre lives and breathes off the dollar. As Chinese control tightens in the Special Administrative Region, we may see an increase in the use of the yuan in its cross-border financial dealings. Furthermore, China continues to expand its operation in the South China Sea and continues to commit human rights violations against its Uyghur Muslim minority. For these reasons, most western democracies will not have the confidence in China to adopt the yuan to the extent Russia has.

It is not only the US’s adversaries that are posing a threat to dollar primacy. As can be seen from Figure 2, the euro is already the dollar’s strongest competitor, making up 20% of central bank holdings against the dollar’s 62%. As US politics has become increasingly dysfunctional, the European Union (EU) has shown unprecedented solidarity by agreeing upon a budget and recovery fund worth €1.82 trillion. For the first time, the bloc will raise €750 billion with collective EU bonds – a reserve instrument that, in time, may be able to match the liquidity and security of US treasuries. Stephen S. Roach of Yale University believes that this fiscal breakthrough will “drive an important wedge between the overvalued US dollar and the undervalued Euro”. Furthermore, the EU has largely succeeded in curtailing the spread of COVID-19 and is planning a large scale “green recovery” as part of its budget. This is in stark contrast to the US, which approaches a fiscal cliff edge as the provisions from the CARES act expire and congress fail to pass further measures. For these reasons, investors are becoming increasingly confident about the prospects for the Eurozone economy. Consequently, the euro has strengthened 9% against the dollar since the recovery fund was first proposed.

The global pandemic also threatens one of the factors that has made the dollar so great – globalisation. Measures taken by governments to curtail the spread of COVID-19 has brought upon the fastest decline in cross border economic activity in history. We have seen unprecedented falls in merchandise trade, foreign direct investment (FDI) and air travel. The outlook for globalisation in the post-COVID world is also bleak. Many US firms will likely decide to re-nationalise supply chains, prioritising resilience to external shocks over efficiency. Firms in key industries such as health and national security may be egged on to do so by the Trump administration, through subsidies for repatriating factories (as seen in Japan). This will disrupt the flow of dollars to manufacturing and export-orientated economies, thereby disrupting the flow of dollars around the world. This sudden shift in the availability of the dollar epitomises what nations like China and Russia fear the most regarding dollar primacy. And thus, it follows that COVID-19 will accelerate the adoption of alternatives to the dollar, whatever form they may take.

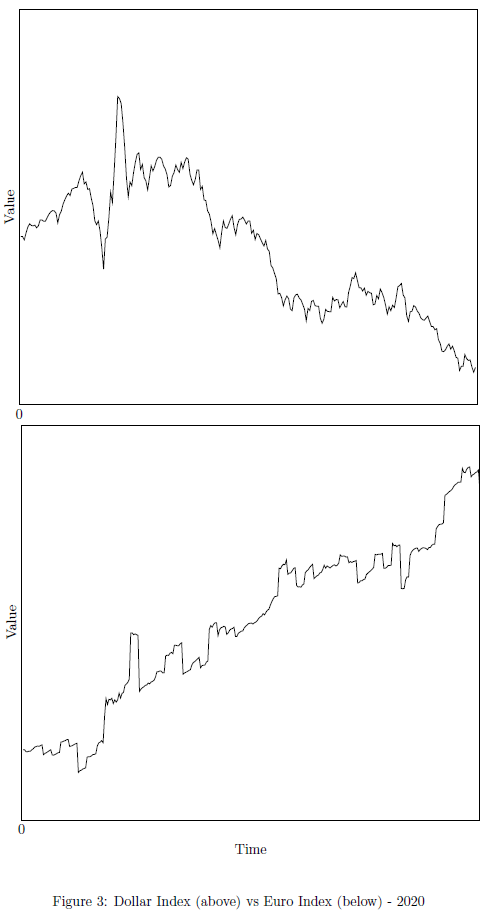

Although COVID-19 does pose a threat to the dollar, there is little chance the pandemic will trigger a total overhaul of the world monetary system. In fact, the pandemic has highlighted many of the dollar’s unique selling points. As the economic implications of the pandemic first became clear, demand for the dollar skyrocketed. This is despite massive deficit spending and the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet that should have theoretically devalued the currency. The DXY index, which measures the dollar against a basket of other currencies, was up by as much as 6.5% from the beginning of the year to March. This shows the extreme, potentially unjustified, confidence in the greenback as a store of value. In conjunction with this, the Fed has acted swiftly and proactively – unlike its colleagues in Capitol Hill – to ensure the smooth running of the global financial system. It “coordinated central bank action to enhance the provision of US dollar liquidity”, arranging bilateral currency swaps and repurchasing facilities with fourteen foreign central banks. No foreign currency – least likely one managed by the CCP – will instil the level of confidence, liquidity and openness required to challenge the dollar. If Americans choose to elect a new president in November, we will most likely see a shift to a less insular form of foreign policy, thereby blunting the long-term effects of COVID-19 on dollar primacy.

The pandemic is exposing – and widening – the cracks in the US’ grip on the global monetary system. Following its March rally, the DXY has fallen by over 10% whilst, in the same time period, the EXY, which measures the euro against a basket of other currencies, is up over 10%. The inertia of the dollar’s dominance, that has prevailed since Bretton Woods, has certainly been disrupted. The unstoppable rise of the dollar in the twentieth century reflected the rise of the current global order and the pre-eminence of the USA, both of which have been brought into question by the pandemic. However, alternatives to the dollar are still in their early stages. It is important to keep in mind that a currency’s utility is largely defined by its existing presence. In this regard, the dollar is virtually unassailable. Therefore, we will not see a sudden ascent to power by a rival currency. Instead, we will see a slow erosion of the dollar’s position at the helm of international finance.