My last post (published over a BA ago) referenced the Keynesian Consumption Function in its approach. The eponym of this laughably oversimplifying economic assumption is largely unknown to those outside of the dismal science. Yet, I believe there exists a compelling argument to consider John Maynard Keynes the next time you’re asked for your dream dinner guest.

Born to a middle class family in Cambridge, Keynes won a scholarship to study at Eton. From there, he returned to Cambridge to study Mathematics at King’s. During this time, he was president of the University Liberal Club, president of the Union, and a member of the University Pitt Club. He was also an active member of the Cambridge Apostles during what many consider to be its heyday. This most secret of Cambridge societies was founded by George Tomlinson (an Olavian-Johnian1 like myself) in 1820 for the most learned of Cantabrigians to engage in highbrow chat. Around a century later, the mother of an Apostle called it a “hotbed of vice” upon discovering her son’s letters. Nevertheless, Keynes’s Cambridge was undeniably a hotbed of intellectual activity. He graduated with a first and continued to be involved with the university for some time, attending economics lectures as a graduate having been urged to do so by the famously sexist economist, Alfred Marshall.

Over the following few decades, Keynes essentially fathered the modern field of macroeconomics. He argued that the government had a role to play in attenuating the business cycle by implementing counter-cyclical policy. Why? Well basically because people don’t like to see the key number on their pay slip go down. Don’t see how these two things are linked? Unfortunately, explaining why in simple terms is beyond my writing and economics abilities. You will have to ask a “macro specialist” – I know one or two who I can get you in touch with if you’re really interested.

Keynes’s magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money essentially made him a post-Depression celebrity. The rejection of the neoliberal laissez-faire paradigm caught on. In April 1942, Keynes joined the Bank of England and in June he was rewarded for his service with a hereditary peerage in the King’s Birthday Honours. He took his seat in the Lords on the Liberal Party benches (don’t let this stop you from reading on).

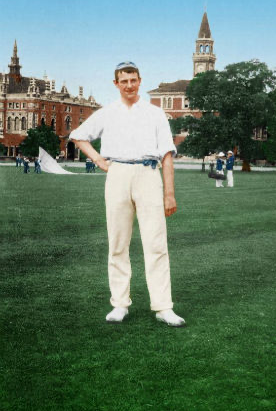

Following the war, Keynes and his idea in The General Theory were crucial in establishing the post-war global order. Keynes was heavily involved, as leader of the British delegation and chairman of the World Bank commission, in the mid-1944 negotiations that established the Bretton Woods system. He also proposed the creation of a common world unit of currency, the bancor and new global institutions. Although these did not materialise immediately, they were essentially manifested in the creation of the IMF and its Special Drawing Rights (SDR) function. Keynes rubbed shoulders (or more likely elbows at his towering height of 6ft 7) with the likes of FDR and negotiated fiercely with Harry Dexter White. He was able to obtain a preferential position for Britain but ultimately failed to implement his ideas globally. Despite this, Keynes was crucial in constructing the global world in which we live today.

This is all very interesting; all very impressive. But it’s Keynes’s views on leisure2 that have really stuck out to me lately. For my own leisure, I picked up some P. G. Wodehouse this Christmas. Envious of Bertie Wooster’s position as a societal drone I was reminded of Keynes’s 1928 essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren. He posits that one day “the economic problem may be solved” and that “for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem-how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him”. Keynes was no stranger to leisure; he had a passion for theatre, ballet, art, literature and philosophy which he shared with the likes of E. M. Forster and Virginia Woolf as a part of the Bloomsbury Set.

I wonder what Keynes would have thought about the recent developments in AI which is most certainly the type of science he anticipated in his essay. For the purpose of this post, let us assume away the bleak complications threatened by AI. I, for one, am hopeful. And I suspect Keynes would share my sentiment; he was considered by many an unbending optimist. He would have been particularly grateful for more time to indulge in the arts with his Bloomsbury chums. Taking a sporting view, I envision the demise of T20 cricket and the return of the superior format to the top of the agenda as hundreds of millions of fans are released from the shackles of work. Although could this go too far? Would these fans start reading through their copies of Wisden at a loss for what to do?