My undergraduate dissertation had the ever catchy title An Investigation into the Effects of Passive Investing on Equity Market Efficiency. I won’t bore you with the results; I certainly won’t bore you with the methods by which I went about getting them.1 Instead, I thought it may be interesting to think about the applications of efficient market theory to non-financial markets.

I had the idea of writing this post when scrolling through Bridge of Highs, an anonymous online submissions page for Johnians where they can share thoughts on a variety of topics. This may range from complaints about rent prices to discussions about classist ent themes (as was the case for an après-ski themed ent). A few recent posts complained about how busy the John’s bar has become on a Friday with a sudden influx of guests from other colleges – a phenomenon which has inspired a campaign coined Jexit. A rather witty comment by a friend wrote “Bar is good on Friday? I’m bringing all of my friends next week”. The comment, deservingly in my opinion, received 20 likes. Although I can appreciate how funny this comment is, my first thought was that this was a brilliant case of how markets deal with information. Unfortunately I didn’t attend the subsequent Friday bar to see how the information was incorporated into market outcomes but I suspect it improved efficiency.

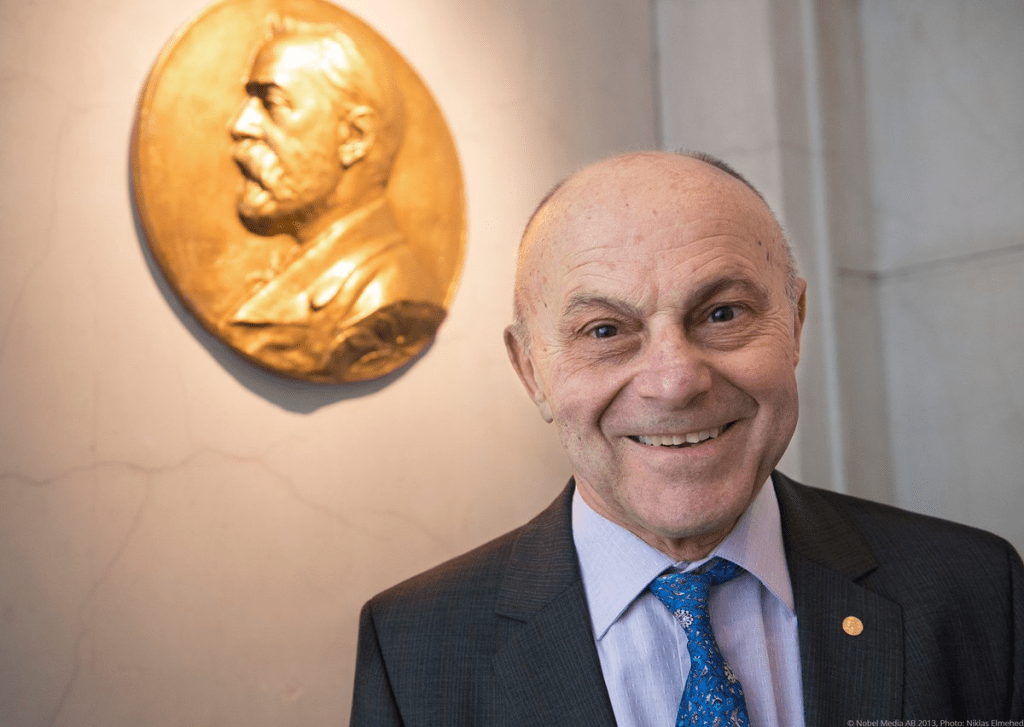

If all this jargon about markets, information and efficiency is confusing, let me explain. In 1970, Eugene Fama, who many consider to be the world’s most influential finance professor, published a paper on efficient capital markets. The paper defines an efficient market as one in which “prices at any time fully reflect all available information”. Consider the stock price of Apple for example. If some information becomes available that the new iPhone is incredibly popular, market participants (in this context, equities traders) will buy the Apple stock. The price of the stock will thereby rise and then new information about the new iPhone’s popularity is now incorporated into the price. The price, therefore, captures all sorts of information about Apple and its stock. Eugene Fama essentially formalised this idea and provided ways of testing for it in capital markets like stock markets, bond markets and derivatives markets. But Fama’s idea doesn’t have to be restricted to such contexts, it can even be applied to the market for cheap booze at St John’s College bar on a Friday night as I alluded to in my exposition.

Fama focussed on prices being a signal for information. In asset markets, changes in demand and supply are almost instantaneously incorporated into prices. This is especially the case for liquid assets with lots of trading volumes, like the case of the Apple stock. However, this isn’t the case for many market. For example, the price of a double G&T at John’s bar has been £4.50 for as long as I can remember – this won’t change on a certain day just because the bar is especially busy. Therefore, focussing on prices in such a market is inappropriate; we must find another measure of efficiency.

I can think of lots of information signals in markets beyond prices: boards displaying the number of available parking spots at a car park, signs estimating the queuing time for a ride at Disney Land and even the Google feature that states how busy a certain venue is at a certain time. In the absence of (flexible) prices, the market has devised its own way of passing information to buyers. But how do we build in the idea of efficiency?

Well classical market efficiency is about how prices adjust to reflect available information. Maybe in such contexts with fixed prices, we may consider how supply and demand adjust (in the absence of a price adjustments) to incorporate new information. Will Google displaying that a certain coffee shop is very busy at a certain time deter customers from going when it’s busy? It probably will, and those who are more averse to long queues and busy spaces are more likely to be deterred than others, thereby improving welfare in the market.

We live in an increasingly information driven world and there has been a recent drive for information to be disseminated to and utilised by the masses. Think about the rising popularity if Polymarket, a cryptocurrency based prediction market that values the incorporation of market participants beliefs into placing odds on events. More widely, think about the current actions of Elon Musk with DOGE, arguing for more transparency over government spending. A recent project by my favourite political magazine, the Spectator Project against Frivolous Funding (or SPAFF) attempts to do the same thing for Britain. Efficient market theory probably remains the most developed framework for thinking about information and I suspect its applications extend beyond just the financial markets.