I recently read Howard Marks’s book The Most Important Thing. For the uninitiated, Marks is a co-founder and co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, the world’s largest distressed debt investment firm. He is known for his memos which are posted publicly on the Oaktree website in which he discusses investment insights, investing strategies and the economy. Amongst his list of accolades, potentially the most notable is a very public endorsement by Warren Buffet who has said “when I see memos from Howard Marks in my mail, they’re the first thing I open and read”. He also happens to have a net worth of c. $2.2 billion. It’s therefore unsurprising that Marks’s book is full of investment gems; it is almost certainly the best book on investing I have read.

Marks’s approach to risk is intuitive and simple, and for me the highlight of his book. It is, however, unorthodox; it differs fundamentally from the notion of risk that many of us (myself included) have been indoctrinated with in undergraduate and graduate finance classes. And the divergence from theoretical financial models is welcome; if understood, Marks’s approach to risk provides actionable investing insight.

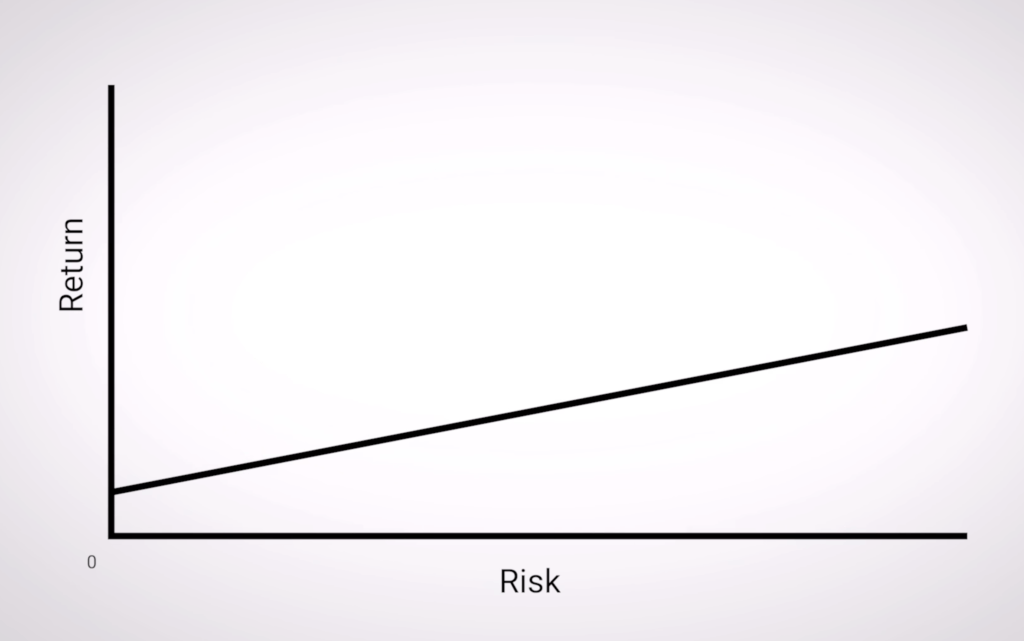

To understand it, we must consider the fundamental relationship in investing: that between risk and return. For an investor to be willing to take on more risk, he must be enticed by more return. Consider the choice between two assets, A and B. A and B both have equal returns but A is riskier than B. We would of course choose to invest in B. This is driven by the fact that we dislike risk; in economic jargon we are risk averse.

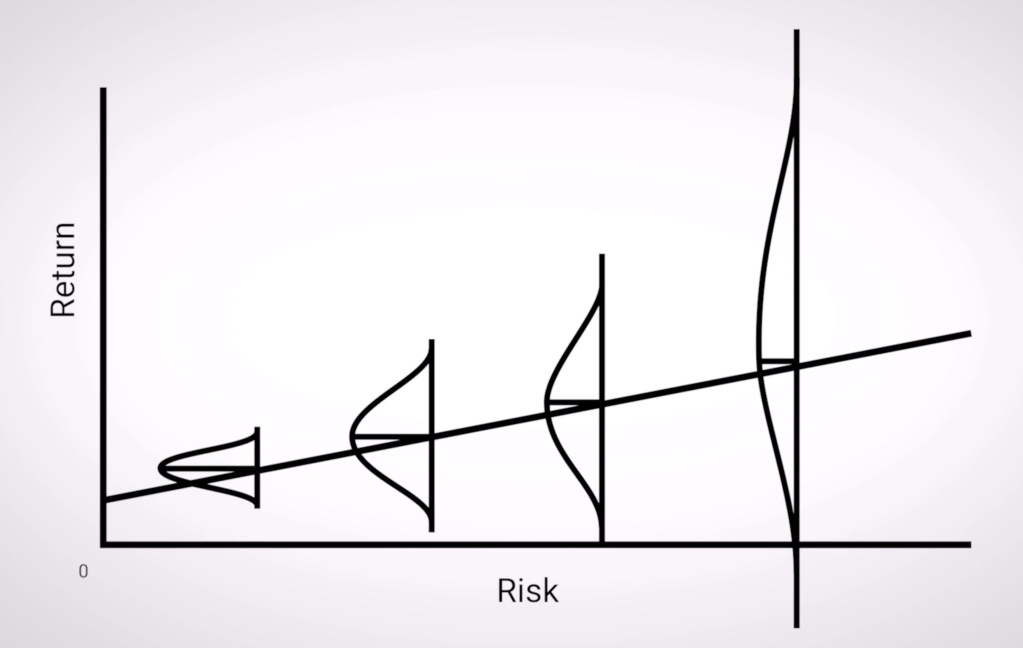

Can you spot the cardinal misnomer I’ve committed in the last paragraph? In place of where I should have said expected returns I’ve instead referred to returns. I misrepresented something which is stochastic as deterministic. More risk doesn’t guarantee higher returns – it just means we can expect higher returns. To quote Marks “there is nothing to say that those higher returns have to materialize”. This is an important idea and can be captured by thinking of the capital market line as in Figure 2 instead of Figure 1.

So far we cannot fault the theory. Finance professors are careful to include expectation symbols before returns in their capital market model derivations. The notion of risk, however, has suffered from simplification to the extent that a layperson’s understanding of risk closely rivals that of a Masters in Finance student entering the asset management industry.

Risk is measured in the theory as variance of returns, Var(R). Variance simply measures the spread of returns and gives academics an easy number to work with. But spread of returns (a.k.a volatility) isn’t really what people think about when they refer to risk. If it is, it isn’t what they mean deep down. Investors don’t demand higher returns from an asset just because it has a higher spread of returns. A higher spread could be biased to higher returns, it could be biased to lower returns. This can be visualised by adding skewness to the vertical distributions in Figure 2. It is clear that the direction of such bias (which we can measure with second order moment, kurtosis) is what investors really care about.1 They demand higher returns because they risk losing money.2 This is what truly drives the risk-return relationship.

Now the final point about risk made by Marks, which I believe is somewhat understated in his book, is that the extent to which investors dislike risk (i.e. their degree of risk aversion) is not static. This is contrary to the assumption often made in financial theory. Marks emphasises that risk aversion varies throughout time and in coordination with the boom-bust cycle. The investment cycle, like the business cycle, is characterised by booms and busts. In the boom phase of a cycle, investors may not demand as much expected return to take on X amount of risk. In other words, their risk aversion is low. In contrast, during a bust investors will demand a higher expected returns to take on the same X amount of risk – risk aversion is high. We can visualise this using the capital market line: the higher investors’ risk aversion, the steeper the capital market line will be. The lower the risk aversion, the shallower the capital market line will be.3 This phenomenon, he believes, provides opportunities for the enlightened investor.

During a bust, varying risk aversion means that rising fear widens risk premiums at the same time that most investors de-risk their portfolios. Marks calls this the “perversity of risk”. The prudent investor would instead add risk to their portfolio when others are de-risking because the premium for doing so is currently high. Again quoting Marks, “when everyone believes something is risky, their unwillingness to buy usually reduces its price to the point where it’s not risky at all”. This, to me, is the one most important piece of investing advice in his book.

When a friend pointed me towards Marks’s book, I took his recommendation, but with a pinch of salt. I said “I do occasionally think that there is no point reading books by people who have done well in finance, especially investing. Because what part of their success is down to being on the far right tail of the distribution by chance”. I was therefore delighted when I found out that chapter 16 of The Most Important Thing is entitled Appreciating the Role of Luck. And for Marks, the proof is in the pudding; Oaktree’s investments in distressed debt in Q4 of 2008 yielded 50-100% in the subsequent 18 months. This is the exact type of trade mentioned above. Marks has talked the talk and walked the walk – a rare thing in the world of finance. I cannot recommend his work enough.

- More astute readers will recognise that this doesn’t stop at second order moments. Even higher order moments are important but the intuition becomes difficult (and superfluous) beyond the second. ↩︎

- I point readers towards semi-variance and the Sortino ratio to measure the risk of loss. ↩︎

- You may also want to think about the intercept of the capital market line with the return axis – the expected return when we don’t take on any risk. This can also change throughout the cycle. This is important but surplus to requirements in the context of this post. ↩︎