This Monday I was lucky enough to watch a spectacular day of Test cricket at Lord’s. Having bought a last-minute ticket on a whim, I was treated to the finale of a five-day nail-biter. The match had everything one would hope for in a Test; marvelous batting, glorious bowling, and a fierce rivalry underpinning the contest which elevated all aspects of the game to the highest level. The match undoubtedly deserves to be remembered as an “absolute classic” – an accolade sparingly bestowed in a format where matches are sadly becoming few and far between. I do hope that this match reignites passions for the long format game; as Sir Geoffrey Boycott put it in a voice note for the Telegraph in his characteristic Yorkshire accent, “T20 can be fun but it has nothing on Test match cricket at its best”.

I had all the time in the world to watch days 1-4 on TV pending my trip to Lord’s. Sitting with Suetonius’s The Twelve Caesars in hand, I probably watched 80% of deliveries on these days. Safe to say I didn’t progress far into the classical epic I had prescribed myself to finish before Sunday evening; I only made it to the end of the chapter on Augustus, who you may know was only The Second Caesar. Despite this, I feel that I used my unique inoccupation wisely. The last time I watched a Test match so fixatedly was the summer of 2011. I vividly remember sweltering in my grandparents’ home in Mt Lavinia, Sri Lanka, watching Alistair Cook knock 294 against India at Edgbaston. I even remember his dismal dismissal: lofting one to Suresh Raina at deep point, having not hit a single six in his 545-ball innings.

Test cricket has evolved significantly since 2011, one often forgotten evolution being the implementation of the Umpire’s Call rule.1 The rule has been prolific in the Anderson-Tendulkar series so far, coming into play eight times in the first three tests. At Lord’s, on-field decisions were upheld on three occasions by Umpire’s Call. This has thrust the rule into the limelight sparking conversation with some muddled takes. Perhaps we can blame the emotion involved in Test match cricket, but nearly a decade on from the ICC’s implementation of Umpire’s Call in 2016, it is time that players, commentators and spectators think deeply about the rule.

Let’s consider one recent comment from which we might identify where the misunderstandings lie. Indian batting legend Sunil Gavaskar was commentating when Joe Root wasn’t given out on-field and the decision remained upon review when ball tracking suggested that it was Umpire’s Call. He said from the commentary box, “You’re saying it was going to kiss the leg stump? There’s no way. It was knocking the leg stump off. The only good thing is that India has not lost the review.”

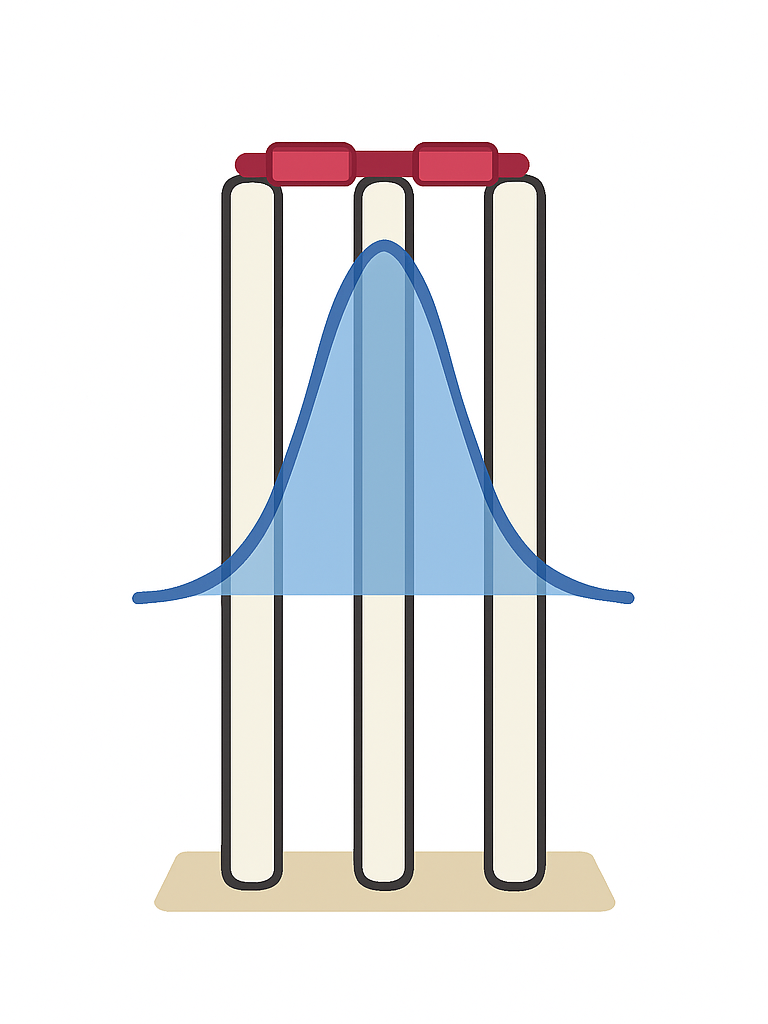

There’s a lot to unpack here but it might be prudent to start with why Umpire’s Call was first introduced in 2016. There are errors involved with all prediction methods and technology.2 Once the ball has hit the pad, ball tracking is no longer doing what is says on the tin – instead it has now turned from tracking to predicting. Every instance of ball prediction, as I will now call it, has some distribution with associated error. When we are shown on the big screen the flight of the ball after it hits the pad, we are being shown the mean prediction. There are a range of other possible flights that could have happened with some probability.

We can think about this with a simple example in which we abstract away the height of the ball and instead focus purely on line. Consider a scenario in which the ball prediction system is 70% certain that the ball would have hit middle stump and 95% certain it would have hit any of the stumps. Assuming symmetry, this gives a 2.5% chance that the ball would have missed leg and a 2.5% chance that the ball would have missed off. In this scenario, it seems reasonable to give the batsman out – we can say with 95% confidence that the ball was going on to hit the stumps. Now transpose this scenario onto the off stump. Now there is a 70% that the ball would have hit the off stump, and less than 15% chance that it would have hit middle or leg. This leaves a 15% chance that the ball would have missed off. Now it seems less reasonable to give the batsman out – we can now only say with 85% confidence (at most) that the ball was hitting the stumps.

If we move the mean prediction around, we can see that at some point it changes from it being reasonable to unreasonable to give someone out off of the ball prediction (given some threshold confidence you want to have i.e. 95%). Umpire’s Call was introduced because the ICC decided that the point at which the mean prediction switches from being reasonable to unreasonable, crossing their chosen confidence threshold for LBW decisions, is when exactly half of the ball is predicted to hit the stumps. They decided that when less than half of the ball was hitting the stumps, the Umpire’s decision was to be trusted – the ICC had more confidence in the Umpire to predict the flight of the ball at this point than the ball prediction system. Hence, we have Umpire’s Call.

Now let’s return to Gavaskar’s comments on Root’s survival by Umpire’s Call. Saying that there was no way a ball was going on to kiss leg stump but was instead going to hit leg plumb indicates a misunderstanding of how Umpire’s Call works. The whole point is that if the ball prediction system predicts that it was kissing leg, we can’t trust it so we defer to the on-field umpire. In this instance the on-field umpire thought it was missing, Gavaskar thought it was hitting; a more appropriate thing to say in the commentary box would be “the Umpire thinks it was going to miss leg stump? No way. It was knocking the leg stump off”. His quibble shouldn’t be directed at DRS, nor Umpire’s Call – rather it should be directed at Paul Reiffel.

Umpire’s Call has played a key role in the Test series between India and England creating frustrating moments for both sides. Commentators must do a better job of conveying to spectators that a deferral to Umpire’s Call is not an arbitrary decision to stand behind umpires but rather one that aims to improve the accuracy of in-game decisions. There exist an abundance of reasons why Test cricket is dying, but one wholly avoidable factor is the perceived highbrow nature of the sport, with its esoteric rules and terminology. We have to minimize this sentiment if we want the format to thrive. Comments like Gavaskar’s, for example, just muddy the waters for spectators new to the game. A large part of the problem with Umpire’s Call has to do with the on-screen DRS graphics that spectators see during a review. The easiest way to explain to someone new to the game what to look for during a review is three reds. I never know where to begin the moment an orange box appears and the inevitable question follows: “Wait — why isn’t that out?”

- The LBW rule essentially states that a batsman can be given out if the ball strikes their legs and would have otherwise gone on to hit the stumps. DRS allows both the batting and fielding sides to challenge the on-field umpire’s decision using ball-tracking technology. Before the introduction of Umpire’s Call in 2016, if any part of the ball was hitting the stumps, the batsman would be given out. After the introduction of Umpire’s Call, what mattered was the centre of the spherically modelled ball. If the centre of the ball was hitting the stumps, then the batsman would be given out. If the centre was outside of the rectangle area of the stumps, technically called the Wicket Zone, meaning less than half the ball was within the rectangle, the original decision of the on-field umpire would remain. ↩︎

- This includes the ball flight prediction an on-field umpire does when making an on-field decision. ↩︎