As a part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, the US Federal government made one time payments directly to households. A relatively high income threshold meant that most Americans were eligible for a payment with adults receiving a payment of $1200 and children receiving $500. The intended effect of these checks was to increase aggregate consumption in the US economy, easing economic decline as a result of the pandemic. We will examine the effectiveness of stimulus checks through the lens of a Keynesian consumption function and Friendman’s permanent income hypothesis (PIH). We will use evidence from households’ spending reports from a Fintech non-profit, a large scale survey of US households and aggregate evidence following the 2001 and 2008 tax rebates.

The Keynesian Consumption Function

Traditional macroeconomic theory would explain how stimulus checks would stimulate the economy through the Keynesian consumption function which takes the following form: C = a + b(Yd) where C is total aggregate consumption, Yd is real disposable income, a is autonomous consumption and b is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC). Stimulus payments, such as those included in the CARES Act, are intended to increase Yd, thus increasing households’ consumption. This will cause an increase in aggregate demand, lessening economic contraction during a recession. From the consumption function it can be seen that the effectiveness of the stimulus checks depends on the size of the MPC, with a larger MPC resulting in a larger increase in consumption (and larger multiplier effect) whilst a smaller MPC results in a smaller increase in consumption (and smaller multiplier effect).

Baker et al. (2020) use high-frequency transaction data from a Fintech non-profit, called SaverLife, to analyse the size of the MPC and how it is affected by income and liquidity. It should be considered that SaverLife users have relatively low income, with average disposable income of $36,000 per annum and median checking account balance of $98. The typical individual in the sample used by the researchers exhibited a rise in mean daily spending from $90 to $250 for the weekdays after receipt of the stimulus, with the increase in spending mostly driven by food and non-durables. The researchers also found that the MPC of SaverLife users varied greatly with level of income, with users having a monthly income above $2000 estimated to have an MPC of 0.325 whilst users with an income below $2000 per month estimated to have an MPC of 0.571. MPC also varied greatly with checking account balance, with users in the 4th quartile of checking account balance having an estimated MPC of 0.256 whilst those in the 1st quartile have an MPC of 0.468. These results may be useful in guiding targeted stimulus measures in the future in order to make stimulus checks more effective.

Coibion et al. (2020) consider a broader sample, using a large-scale survey of US consumers to study how stimulus checks affected consumption. When asked to break down how US households spent (or planned to spend) their checks, on average around 30% was saved, 30% was used to pay existing debts and the remaining 40% was spent on consumption. In short Coibon found that the average MPC out of stimulus payments was little over 0.4 with almost 40% of respondents having a MPC of 0.

Therefore, we can see that both the data from SaverLife and the large scale survey suggest that the MPC out of stimulus payments was low, reducing the effectiveness of the policy. We can potentially explain this by using the permanent income hypothesis.

The Permanent Income Hypothesis

Unlike the Keynesian consumption function, which believes that current levels of consumption depend only on current levels of income, Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis believes that consumers consider expected future levels of income when deciding what proportion of their marginal income to spend on consumption. Under the PIH model, a temporary increase in income will only result in a small increase in present consumption as future income expectations are unimpacted. Consumers will save the majority of the temporary increase in income to smooth consumption in the future. The model requires a rise in permanent income (long-term expected income) for consumption to rise. This may arise from an increase in wage levels or the introduction of a universal basic income for example. Therefore, the PIH model predicts that stimulus checks, a form of temporary income, will have little effect on current levels of consumption.

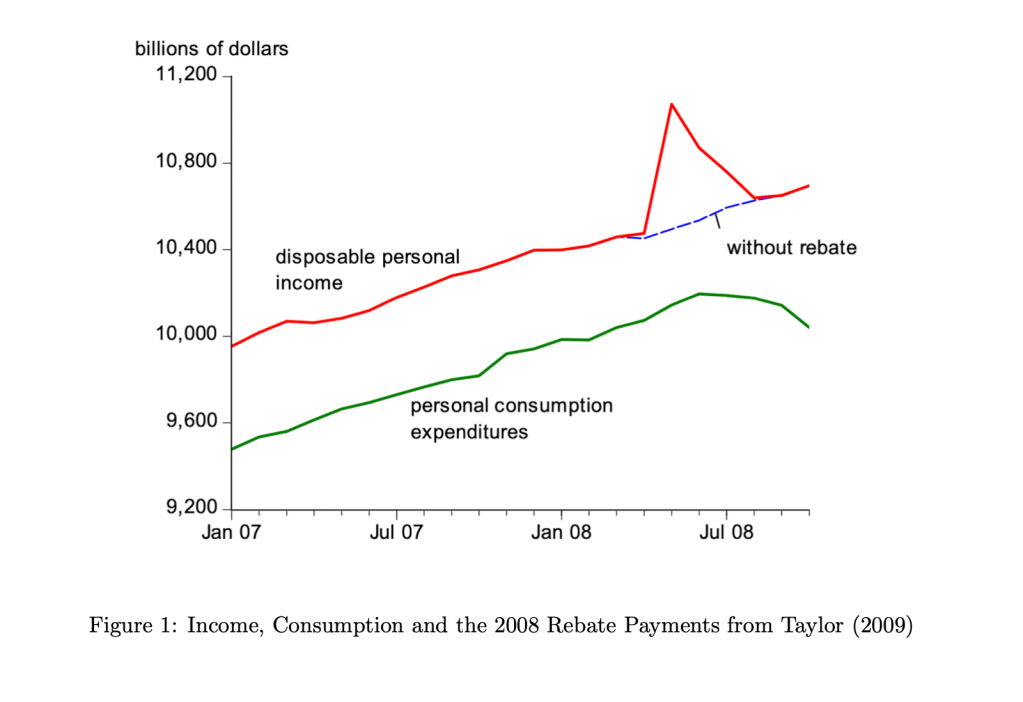

We can look at aggregate consumption data following tax rebates in 2001 and 2008 to confirm these predictions. In May of 2008, as part of the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, tax rebates were made to households. Figure 1 shows that the temporary rebate had little to no effect on aggregate consumption. A more formal regression technique by Taylor (2009), which corrected for changes in oil prices, also found the rebates to be insignificant. When Taylor conducted a regression using disposable income minus the rebate (permanent income) he found the increase in consumption to be statistically significant. These findings are consistent with the PIH model.

As part of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001, most American taxpayers received checks of up to $300 per individual. Shapiro and Slemrod (2003) used surveys to look for evidence of lagged responses. Of those who initially said they would mostly save their rebate, 93.4% said that they would try to keep up a higher saving (or lower debt) for at least a year, when asked 6 months later.1 This is consistent with the PIH model. Shapiro and Slemrod (2009) carried out a similar survey in 2008, in which only 18% of those who said they were saving the rebate said they would spend it later. Therefore, in both 2001 and 2008 consumers did not expect to spend their rebates. This is consistent with the predictions of the PIH model as consumers would only spend if increases in income were permanent.

Conclusion

It is clear from the evidence used that stimulus checks are ineffective at stimulating aggregate consumption, as past uses of stimulus checks have rendered low MPCs which can be explained through the PIH. This low MPC means that the aggregate effect of the policy is low (due to a small multiplier effect) and also means that the policy provides little “bang for the buck” when fiscal resources are scarce. In the future it may be possible to target such stimulus at those with lower liquidity or income who exhibit higher MPCs. Despite this MPCs will still remain relatively low due to the income being temporary. Instead, policies that increase wages, a form of permanent income, should be considered.

One reply on “How Effective are Stimulus Checks?”

A very informative and well explained article

LikeLike